Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, the student should:

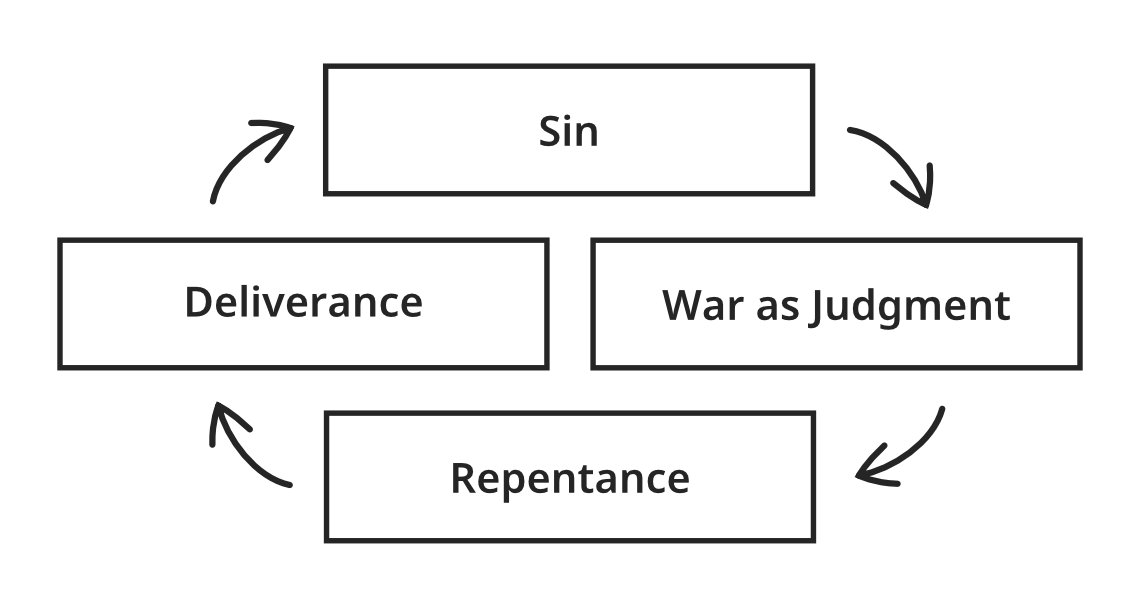

(1) Be able to outline the primary themes of Joshua, Judges, and Ruth.

(2) Know the major events of the conquest of Canaan and the period of the judges.

(3) Recognize the importance of preparation for the transfer of leadership.

(4) Understand the concept of Yahweh War in Joshua.

(5) Relate the messages of Joshua, Judges, and Ruth to the needs of today’s world.